In the fall of 2009, I got to go on an epic caving weekend near the Montana-Wyoming border. I talked briefly about some interesting chert nodules here, but I was honestly holding out on the best stuff: the formations.

In the fall of 2009, I got to go on an epic caving weekend near the Montana-Wyoming border. I talked briefly about some interesting chert nodules here, but I was honestly holding out on the best stuff: the formations.The caves here are formed in the limestones and dolomites of the Madison group. These rocks formed between 360 to 325 million years ago, in the Mississippian, when a relatively tranquil, shallow sea covered the area. Like most seas, this one was filled with small organisms that had calcium shells or skeletons (such as corals or amoeboids.) When these organisms died, their decaying corpses were slowly compressed into limestone. Above the limestone lies a layer of reddish sandstone called the Amsden laid down in the Pennsylvanian, visible as the red streak in the above picture. After undergoing a sequence of uplift and subsidence, it was uplifted to its current level during the Laramide orogeny, about 70 million years ago. This created joints in the limestone that would someday become caves.

(It’s a really structurally interesting area – some of the nearby mountains are uplifted in a giant anticline, while the ones in the above picture are fault blocks that were tilted upwards.)

The Madison group stretches from South Dakota to eastern Idaho, and from Canada down into Colorado and Arizona, although the name differs regionally. Since limestone is very soluble, it’s chock-a-block with caves, including Lewis and Clark Caverns in Montana. Because of its solubility, it forms a very important aquifer, and has produced a prodigious amount of oil – over 1,400,000,000 barrels. (Pretty impressive for a bunch of dead sea critters!)

These caves were eroded as the basin lay beneath the water table, in a process called phreatic erosion. Phreatic erosion occurs as the water flows through cracks and joints, eroding passages through the limestone. This passageways travel in all directions: the above photo shows a vertical, cream colored passage cutting through different bedding planes. Additionally, we saw some collapse along bedding planes, which created some fantastic flat roofs, visible here in the greyish section. Dating caves can be difficult (much like men), however some ash found in these caves is from an Yellowstone eruption 640 thousand years ago.

These caves were eroded as the basin lay beneath the water table, in a process called phreatic erosion. Phreatic erosion occurs as the water flows through cracks and joints, eroding passages through the limestone. This passageways travel in all directions: the above photo shows a vertical, cream colored passage cutting through different bedding planes. Additionally, we saw some collapse along bedding planes, which created some fantastic flat roofs, visible here in the greyish section. Dating caves can be difficult (much like men), however some ash found in these caves is from an Yellowstone eruption 640 thousand years ago.(I apologize for the poor picture – it’s quite difficult to take decent photos of large cave rooms without secondary light sources.)

This is a trace fossil we found on one of the bedding plane ceilings – it’s where a sea creature was burrowing, or eating, or squirming along. (The paleontologist on the trip provided some more details, but I’ve unfortunately forgotten.) I had never seen a fossil in the wild before, so this was one of the trip’s highlights.

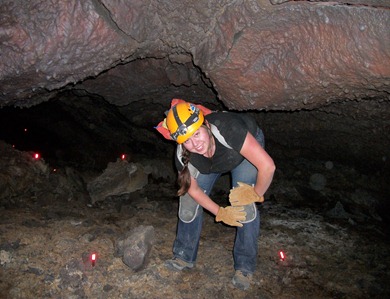

This is a trace fossil we found on one of the bedding plane ceilings – it’s where a sea creature was burrowing, or eating, or squirming along. (The paleontologist on the trip provided some more details, but I’ve unfortunately forgotten.) I had never seen a fossil in the wild before, so this was one of the trip’s highlights.The first cave we went to is the most challenging cave I’ve been in so far, despite being entirely horizontal. The entrance is through a 100’ long crawlway – which sometimes is only 15” tall. (I definitely got stuck a couple times!) The floor of this crawlway is thickly coated with radon-laden dust: to avoid developing radioactive cavers, the BLM limits the time you can spend in the cave each year. We wore dust masks, to cut down on the amount of junk we inhaled, but that only served to make me more claustrophobic. This was even more heightened by the heat – it was the warmest cave I’ve ever been in. It was a pretty rough beginning, but we were richly rewarded for all that effort with masses and masses of my favorite formation – helictites.

I didn’t have my camera that day, but I did the next day, when we visited the second cave. The day of this trip, snow was predicted, so we only spent the morning underground. (The road to the caves requires a 4wd vehicle generally, but is reportedly impassable in bad weather.) Luckily, as we ascended out of the cave right as the snow began falling, and made it to paved roads just in time.

The caves have a wide variety of calcite formations, including helictites, rafts, and some really large cave popcorn. Additionally, they have gypsum flowers and crusts, epsomite crystal curls, and aragonite needles. These all form near each other, making for some truly impressive photographs.

The caves have a wide variety of calcite formations, including helictites, rafts, and some really large cave popcorn. Additionally, they have gypsum flowers and crusts, epsomite crystal curls, and aragonite needles. These all form near each other, making for some truly impressive photographs.

This last photograph is an interesting chunk of yellow and red crystal crust that was forming in a hole in the ground. I still don’t know what it is…

This last photograph is an interesting chunk of yellow and red crystal crust that was forming in a hole in the ground. I still don’t know what it is… This is the underside of a rock, absolutely encrusted with black crystals.

This is the underside of a rock, absolutely encrusted with black crystals. As we headed back to civilization, there was an antelope hanging out, clueless about what lay beneath its small cloven hoofs.

As we headed back to civilization, there was an antelope hanging out, clueless about what lay beneath its small cloven hoofs.

![MantisCeiling_thumb[1] MantisCeiling_thumb[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEixv3T2nKPw0za3tJN20xDeHU-lZnjjsWkt7sXkuixrakWlYDFUBt1DIN4elfJs2I_HoszkkCjbQj-z7VUF7B3wfOO-RMp8H90kfmmGV3fvhwlQ9ZW-TXaIQ9XlLfP9fgM0R9eyzGz9VEM/?imgmax=800)

![IMG_2763_thumb[1] IMG_2763_thumb[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgNXFo9WmnnVvGN_Q4DqHyJFIiy4XT9dMBXh8CCHZG-qpDyVTWTH6Iw6Hus_FbCl_wlW5K0Q2XfwzFyD8pF92JG__I-ZfKB4FUrodijHaTv74Q1mBSw8Fk2Aj-pZHveAxrRLVh6JTvHHzQ/?imgmax=800)

![IMG_2817_thumb[1] IMG_2817_thumb[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgGq61CEpaV5D2zIkZ5jmAY8kJ6F-oLNjRUuLnmMHQxsvN1mnUhmQ7_4ZUcBNO4TR1fPJKco-0CzoeRcWhBnmR3t44qVvCdl5lgh2izbcTpmFUONIuAvTDRj1Ny9G83nppOkVHBPM8N4N0/?imgmax=800)